A whaling ship Caroline was recorded transporting flax, whale oil, and seal blubber from New Zealand to Sydney in 1830.

Timaru was a hub for whalers and traders in the 1830s, with the Weller Brothers setting up a whaling station here at Caroline Bay in 1839.

Caroline Bay could have been named after a whale supply ship, though there were a few ships with the same name at the time.

Ships were often named after royalty, and Caroline might refer to Queen Caroline of Brunswick (1768-1821), wife of King George IV. She became Queen of the United Kingdom and Hanover in 1820. She was popular with the British people because George insisted on a divorce, which she refused.

When the whalers arrived there was a Māori hut on the stony beach constructed of whale bone and tussock. The Weller brothers established whaling stations, one at Whalers Creek, later named Caroline Bay after a whaling supply ship. According to the Record of Settlement book, The Timaru whaling station, operated by the Weller Brothers, produced 70 tuns of oil (approximately 17,640 gallons or 66,780 liters) during the 1839 season, marking a highly successful start. In 1840, the station yielded 65 tuns of oil (around 16,380 gallons or 62,010 liters), bringing the total production over two seasons to 135 tuns (about 34,020 gallons or 128,790 liters), which was likely shipped to markets such as Sydney for sale. However, the station was abandoned in 1841 following the financial failure of the Weller Brothers, ending Timaru's brief but productive whaling era.

"70 tun was ready to be collected at Timaru station". A tun of oil is by volume, 1 tun = 8 barrels. A wine tun is 252 gallons. Signwriting was incorporated to cargo of the shipwreck to intrigue visitors into learning more about the stories that inspired the playground. One barrel is a nod to the first known shipment of whale oil that was at Caroline Bay waiting to be collected. The other barrel is a nod to Timaru's first shipwreck the Prince Consort. William Williams, the first European born in Timaru, was the son of Samuel William, also known as "Yankie Sam," a whaler who had joined a whaling gang in the area in 1839. In 1886, Samuel Williams returned to Timaru to work for Rhodes, where he ran a small accommodation house and became the town's first publican. An interesting piece of local history is that his son's cradle was made from a gin crate. - Photo Roselyn Fauth

LEFT A try pot used at the Weller Bros Whaling Station near this place 1839-1840. The Wellers’ workers caught whales and rendered the blubber down into oil in try pots for two seasons Members of the whaling gang were the first white men to live even temporarily in South Canterbury. RIGHT Looking up towards the viaduct near the Evans St and Wai-iti Rd intersection where the stream runs underground. Photograph courtesy of Roselyn Fauth

Timaru's early history is deeply intertwined with the whaling industry, which played a significant role in the development of the town and its economy. The sheltered bays and coastline were ideal for whaling stations, where crews would process the whales they hunted. The town’s most iconic spot, Caroline Bay, some say, could be named after the Caroline whaling ship, one of the early vessels to operate in the region during the 19th century.

Let's go on a whale hunt!

The name Caroline may derive from an early whaling ship used to drop off supplies and pick up whale oil. Most likely the Barque Caroline that was recorded at Lyttelton Harbour in September 1836. Can you point to a sign with “Caroline Bay”?

The Weller Brothers had their whaling station from 1839-1841. A whale pot stands at Pohatukoko Stream, known as Whale’s Creek. Can you stand above the pipe under ground?

Find the whale pot at Patiti Point

Visit Whale Bone Corner at Claremont

The Whaling Station at Timaru Timaru was home to one of the first whaling stations established in the 1830s. Whalers came from Sydney, Port Underwood, and other parts of New Zealand to hunt sperm whales. The process of whaling was a huge industry that brought European settlers and Māori together, each contributing to the success of the whaling station.

Caroline Bay

Named after the Caroline whaling ship, Caroline Bay holds historical significance in the whaling industry. The bay became a central point for whalers, where ships like the Caroline were moored while they processed their catches. It was also the location for many of the whaling station facilities, such as the casks and try-pots used to process whale oil.

Whalers and Their Legacy in Timaru The whalers in Timaru were brave men who risked their lives in dangerous conditions to hunt whales for their oil, which was used for lighting lamps, making soap, and many other purposes. Over time, as whaling declined and other industries took over, the whalers became part of the history and the local culture. They not only brought European customs to the region but also worked closely with Māori communities, whose knowledge of the land and sea was invaluable to the whaling efforts.

Shipwrecks and Challenges at Sea One of the most significant early maritime events in Timaru was the wreck of the Prince Consort in 1866. This 35-ton schooner, having arrived from Lyttelton, was struck by powerful waves during strong northeast winds, capsizing off the coast near the whaling station. While the crew was fortunate to survive, the wreck of the Prince Consort serves as a reminder of the perilous conditions faced by those who relied on the sea for their livelihood.

The Playground and Its Connection to Whaling History The playground at Caroline Bay, near the old whaling station, provides a unique opportunity to learn about the town's rich maritime history. The area where the playground sits was once central to the whaling industry, and the historic site still echoes the legacy of the whalers.

One of the special features of the playground is the barrel inside the ship structure, a nod to the tools used by whalers. The barrel represents the whale oil casks used to store the oil extracted from whales. The ship structure itself is a playful yet educational way for children to engage with Timaru's whaling past, giving them a hands-on understanding of how whalers used to live and work.

The ship barrel inside the playground also reminds us of the essential role that whaling played in shaping the region. By understanding the significance of the whaling industry, children can appreciate how the past impacts their present surroundings.

The Significance of Place Names: Caroline Bay and Beyond

- Caroline Bay: Named after the Caroline whaling ship, which was a pivotal part of Timaru's whaling history.

- Patiti Point: This point, just near the playground, is another historical location where whalers worked and processed their catches.

- Pohatukoko: The northern reef at Timaru Harbor, known by Māori, was also crucial to the whaling activities in the region.

Activities for Students

-

Historical Inquiry:

- Ask students to research the role of the Caroline whaling ship and its significance in Timaru's whaling history.

- Discuss the connection between whaling and the naming of Caroline Bay.

-

Shipwreck Exploration:

- Have students look into the shipwreck of the Prince Consort and explore the dangers faced by early sailors.

- Create a timeline of significant maritime events in Timaru’s history.

-

Creative Play:

- Have students create their own whaling ship designs or replicas, using materials such as cardboard or wood.

- Discuss the tools that whalers would have used and how they would have operated a whaling station.

-

Mapping the Past:

- Use historical maps and modern maps to help students locate Caroline Bay, Patiti Point, and other significant places related to Timaru's whaling history.

The whaling industry played a vital role in shaping Timaru’s early economy and development. From the whaling ships that gave Caroline Bay its name, to the wreck of the Prince Consort, the history of the sea is still alive in the town. The playground near the whaling station and the ship barrel inside the ship structure are reminders of this fascinating past. By understanding these stories, students can better appreciate the local heritage and the ways in which history influences our surroundings.

References for Further Reading:

- The Whalers of Timaru by R. Campbell

- Shipwrecks of New Zealand by J. Smith

- Timaru Historical Journals (Online Archives)

Whaling History in Timaru (Based on the PDF)

- Early Whaling Activity:

- Whaling in Timaru began in the 1830s, with the first recorded mention of a whaling station in March 1839 in the Harwood Journal.

- The Weller Brothers, a prominent whaling firm based in Otago, established a whaling station at Timaru as part of their network of shore stations.

- Whaling Stations:

- The main whaling station was located at Scarborough (Motumotu), about four miles south of Timaru Flat.

- Another station was situated between Queen and Mill Streets, near the present-day Timaru Harbour, which was used as a landing place for whalers.

- A third station was at Patti Point, though its exact operational status is less clear, as it may have been more residential than functional.

- Whaling Operations:

- The Dublin Packet, a schooner owned by the Weller Brothers, transported whaling gear and personnel to Timaru in March 1839.

- The station at Timaru was highly successful, producing 70 tuns of oil in the 1839 season and 65 tuns in 1840.

- Whalers used try-pots to boil whale blubber into oil, and the remains of these operations, including broken boilers and decayed oil barrels, were noted by visitors like Bishop Selwyn in 1844.

- Personnel:

- Thomas Brown was the overseer of the Timaru whaling station, leading a gang of about 16 men, including Samuel Williams, a boat-steerer.

- Other notable figures included Philip Ryan, the cooper, and Joseph Price, who was associated with the Harriet, a ship linked to the whaling operations.

- Land Purchases:

- In 1839, the Weller Brothers purchased land from Golok, a Maori chief, for a whaleboat, clothing, and other goods. This land extended from the Waitaki River to Banks Peninsula.

- They also bought Timaru Flat from Tuhawaiki (Bloody Jack), a prominent Maori chief, for £10 in 1840, though this land was later identified as being near Taumutu, not Timaru.

- Decline of Whaling:

- The Timaru whaling station was abandoned by 1841, following the financial failure of the Weller Brothers.

- The station was described as "deserted" by Bishop Selwyn in 1844, with dilapidated try-works, broken boilers, and decayed oil barrels scattered around.

- Maori Involvement:

- Maori chiefs like Golok and Tuhawaiki played a significant role in facilitating whaling operations by selling land to the Wellers.

- Maori workers were also employed at the stations, with names like Tomahawk and Rootie mentioned in the Harwood Journal.

- Legacy:

- The whaling industry left a lasting impact on Timaru, with place names like Caroline Bay (named after the whaling barque Caroline) and Whalers' Lookout reflecting this history.

- Remnants of whaling, such as try-pots and whalebones, were still visible in the mid-19th century, as noted by visitors like Edward Shortland and Walter Mantell.

- Historical Significance:

- Whaling was one of the earliest European economic activities in Timaru, predating agricultural settlement.

- The industry attracted a mix of European and Maori workers, creating a unique cultural and economic dynamic in the region.

This summary captures the key points about the whaling history in Timaru as detailed in the PDF: Hall-Jones, Frederick George., Early Timaru: some historical records of the pre-settlement period, annotated and analysed.. Aoraki Heritage Collection, accessed 01/03/2025, https://aorakiheritage.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/161

Hall-Jones, Frederick George., Early Timaru: some historical records of the pre-settlement period, annotated and analysed.. Aoraki Heritage Collection, accessed 01/03/2025, https://aorakiheritage.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/161

Whalebone Corner: Corner of Taiko, Claremont and Fairview Roads, west of Timaru. This intersection is known as 'Whalebones Corner'. Ever thought, if I stuck some whale bones near my house, it would make it easier to find? Worn by weather for over 100 years, you can see the remnants of four whale bones which were brought out from the whaling station on Caroline Bay about 1870. Mr John Machintoch, who built the house on the farm Kingsborough about the tome instructed John Webster to collect the bones on a dray and to place them a the intersection so the visitors could be easily directed to Kingsborough. Since then, this intersection has always been known as The Whalebones Corner. (Take care is stopping here and park well away from the intersection).

Medinella Fauth with a piece of whale bone found at Patiti Point - Photo Roselyn Fauth

Standed whale at Patiti Point Timaru - Geoff Cloake

Saving a whale at Caroline Bay - Geoff Cloake

Whale stranded at Caroline Bay - Geoff Cloake

Humpback Whale-Geoff Cloake

Grave of Timaru Whaler, Samuel Willams (Yankie Sam). He died at Timaru onHe died at Timaru onJune 29, 1883, at the age of 64- A bluestone monument, apparentlyerected by his fellow citizens, describes him as the oldestresident of Timaru.

-

Samuel Williams was a boat-steerer at the Timaru whaling station during the early 19th century, as recorded in the Harwood Journal.

-

He was part of Thomas Brown's gang, which operated at the Timaru whaling station in the late 1830s and early 1840s.

-

Williams was one of the 16 men listed in Thomas Brown's gang, which included other notable figures such as Peter Johnson, Charles Watkins, and William Mozzaroni.

-

He was among the early European settlers in Timaru, arriving during the whaling period before the formal settlement of the area.

-

Williams later became associated with the Timaru Hotel, indicating his transition from whaling to other occupations as the settlement grew.

-

He was described as the oldest resident of Timaru at the time of his death, having lived through the early whaling days and the subsequent development of the town.

-

Williams died on June 29, 1883, at the age of 64, and was commemorated with a bluestone monument erected by his fellow citizens.

-

His connection to Timaru is significant as he was one of the few individuals who bridged the gap between the pre-settlement whaling era and the later agricultural and urban development of the town.

-

Williams' presence in Timaru is documented in both the Harwood Journal and the Jubilee History of South Canterbury, highlighting his role in the early history of the region.

-

His experiences as a whaler and later as a hotelier provide a glimpse into the transitional period of Timaru from a whaling station to a settled community.

-

Williams' life and contributions are emblematic of the early European influence in Timaru, marking him as a key figure in the town's historical narrative.

- Hall-Jones, Frederick George., Early Timaru: some historical records of the pre-settlement period, annotated and analysed.. Aoraki Heritage Collection, accessed 01/03/2025, https://aorakiheritage.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/161

Caroline Bay naming

Yes, the PDF provides some information about the whaling ship Caroline, which is connected to the history of Timaru and the broader whaling industry in New Zealand. Here are the key details:

Caroline Bay:

- The name Caroline Bay in Timaru is believed to have been derived from the whaling barque Caroline, which was owned by the Sydney firm R. Campbell and Company.

- The Caroline was one of the earliest whaling ships to operate in the region, engaging in bay whaling along the New Zealand coast.

Early Operations:

- In the early 1830s, the Caroline was captained by Blenkinsopp, who was based at Port Underwood in Cloudy Bay, New Zealand.

- In 1834, Blenkinsopp used the Caroline to transport several escaped convicts from Sydney to his shore station in New Zealand.

Later Captains and Ownership:

- After Blenkinsopp, the Caroline was captained by Cherry, who was later killed by Maori near Mana Island.

- The ship was subsequently commanded by James Bruce.

- In 1837, the Caroline was purchased by John Jones, a prominent figure in the New Zealand whaling industry, who operated several shore stations from Waikouaiti to Preservation Inlet.

Possible Wreck:

- The Caroline may have been the same 400-ton barque that was wrecked at New River Heads on April 1, 1860.

- This ship had been purchased by Jones, Cargill, and Company, who intended to convert it into a store ship at Invercargill.

Legacy in Timaru:

- The name Caroline Bay in Timaru is a lasting reminder of the ship's influence on the region's whaling history.

- A try-pot from the whaling era, found near Patti Point, is now displayed at Caroline Bay, further connecting the area to its whaling past.

The Caroline was a significant whaling ship that operated in New Zealand waters during the 1830s, contributing to the early whaling industry in Timaru and other regions. Its legacy is preserved in the name Caroline Bay, and its history reflects the broader impact of whaling on New Zealand's coastal communities.

- Nomenclature section (pages 60-61) for the details about the whaling ship Caroline and its connection to Timaru.

Early Timaru: Some Historical Records of the Pre-Settlement Period, Annotated and Analysed"

By F.G. Hall-Jones

Published in 1956 by the Southland Historical Committee

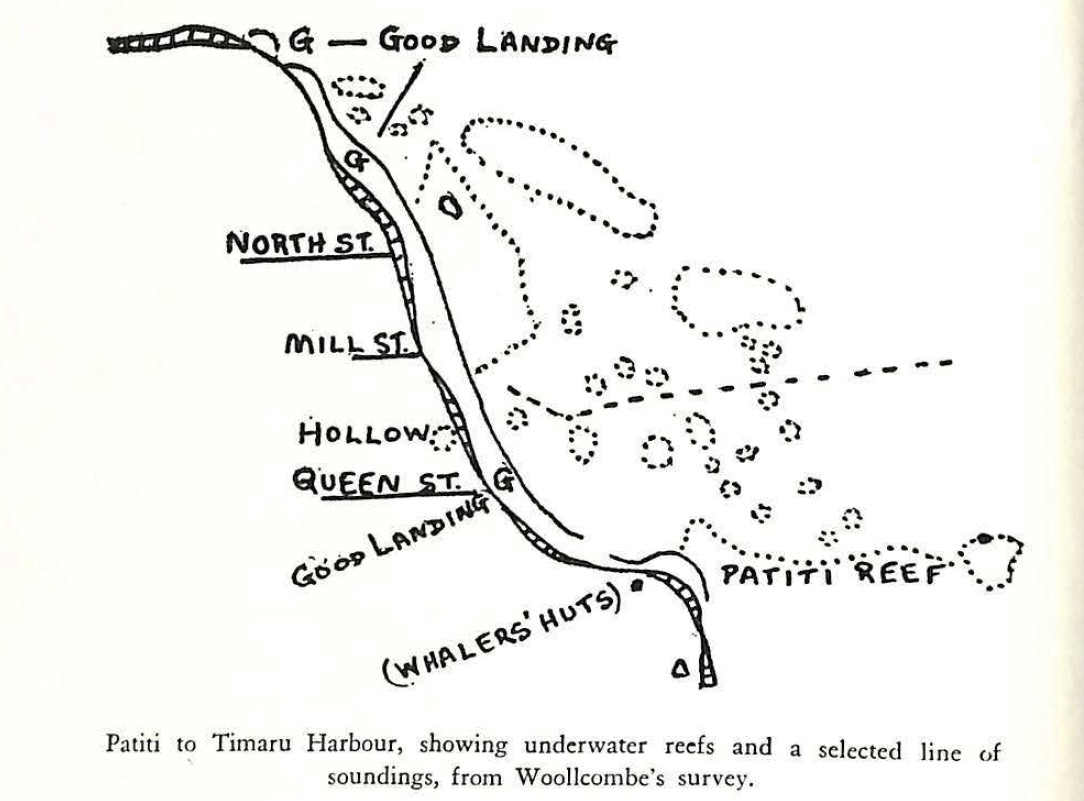

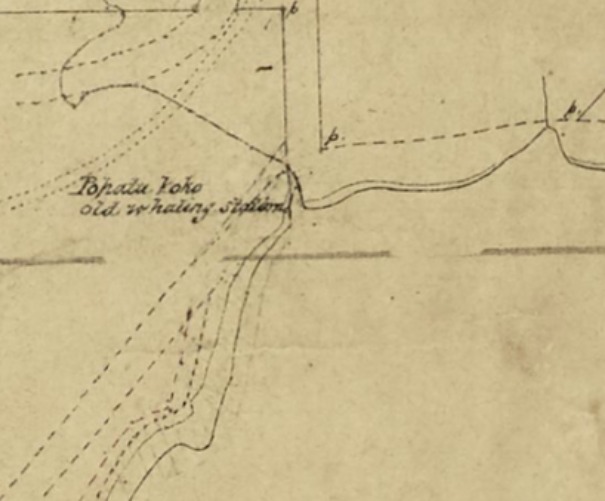

Early Timaru Book by F. G.. Hall-Jones. Cover and inside page: North Street to Maori Reserve. After A. Wills, 1848 (re-worded). An old map gives Pohatukoko, the same name as the northernAn old map gives Pohatukoko, the same name as the northernreef at the harbour, at the head of the bay on the site ofthe old native huts shown on Wills's map.

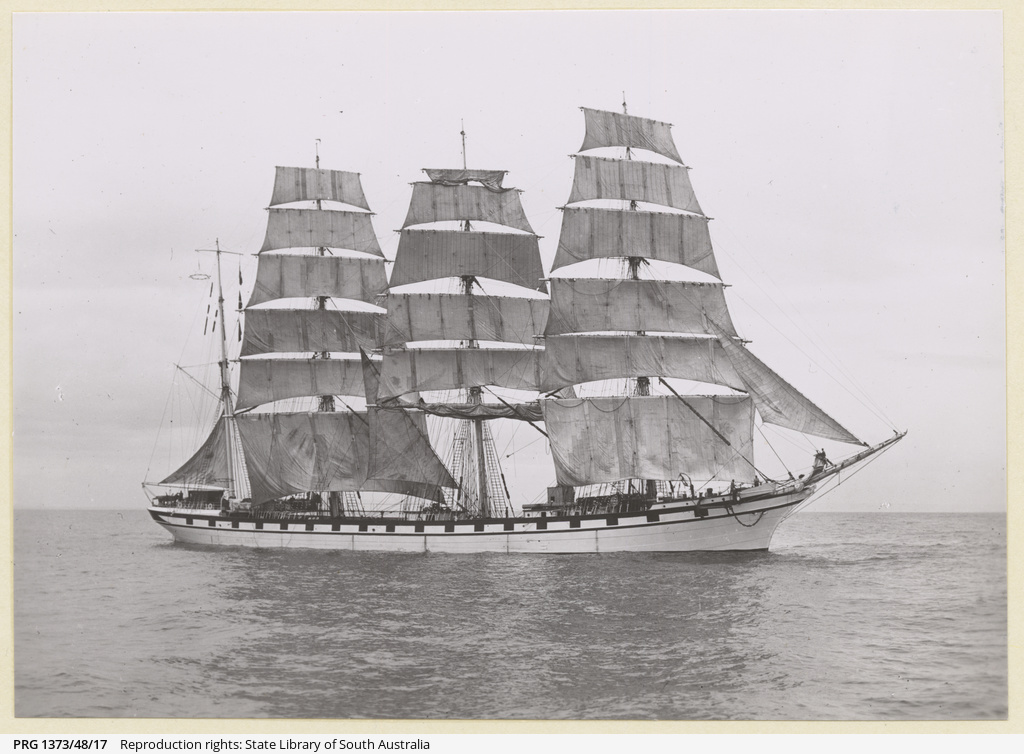

A black-and-white photograph of the Caroline, a steel 4-masted barque weighing 2,357 tons. Built in 1891 by Richardson, Duck and Co. of Stockton, the ship measures 300.5 feet in length, 42 feet in breadth, and 24.7 feet in depth. Originally registered in Windsor, Nova Scotia, Caroline was owned by FC Mahon before being sold in 1908 to Antoine Dom Bordes of Dunkirk and renamed. Known for its fast passages in its early career, the vessel tragically caught fire and was beached at Antofagasta in July 1920. This image is part of the A.D. Edwardes Collection, which includes photographs of sailing ships taken between 1865 and 1920. It was digitized on October 1, 2019, and is held by the State Library.

Part of the A.D. Edwardes Collection, specifically from a volume titled 'French Owned Shipping Lines'.

No known copyright restrictions. Please refer to the State Library's Conditions of use for more details.

https://collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/resource/PRG+1373/48/17

Some of the earliest Europeans to arrive in the area were also whalers. Their existence was rough and their work extremely dangerous, a far cry from what we could imagine living in the city today.

The dutch explorer Abel Tasman is officially recognised as the first European to 'discover' New Zealand in 1642.

The French were among the earlier European settlers in New Zealand, and established a colony at Akaroa in the South Island in 1830s.

Sealers were some of the first Europeans to visit the coastal regions around Timaru in the late 18th century. They were attracted to the area by the abundance of fur seals which they hunted for their valuable pelts. The exact dates of their visits are not well documented.

Europeans of all descriptions came to New Zealand during this time — Dutch, French, Russian, German, Spanish, Portuguese and British, as well as North Americans.

"They encountered a Maori world. Contact was regional in its nature; many Maori had no contact with Europeans. Where contact did occur, Europeans had to work out a satisfactory arrangement with Maori, who were often needed to provide local knowledge, food, resources, companionship, labour and, most important of all, guarantee the newcomers' safety. Maori were quick to recognise the economic benefits to be gained in developing a relationship with these newcomers... . Some Maori joined whaling vessels as crew and Sydney became the most visited overseas destination for Maori." - nzhistory.govt.nz/sealers-and-whalers

In 1839 The Weller Brothers established a whaling station at what is now the corner of Evans St and Wai-iti Rd. Samuel Williams was the leader of this party, and boat steerer and harpooner at the new station. The layout of the land was different from what we could imagine then too.

The whalers described the area of gently undulating, tussock-covered downs cut by watercourse on their way down to a boulder-strewn beach. Between the valleys rose clay loess cliffs, and reefs that extended into the sea providing safe openings for ship protection. North and South lagoons extended far inland, and the only trees were cabbage trees.

They set up camp near Pohatu-koko stream, which they nicknamed ‘Whaler’s Creek’ (see ‘South Canterbury: A Record of Settlement’ by Oliver A. Gillespie, 1958, p39). Pohatu-koko shows up on some of the earliest maps of the area, but isn’t as well known today now that it runs underground.

The whalers are also rumoured to have given Caroline Bay its name too. The name first appears in descriptions of the sale by Māori to the Weller brothers of more than one million acres of land on 4 Dec 1839. Some say it was named ‘Caroline’ after the ship that came to pick up the whale oil. The ship "Caroline" regularly dropped anchor after the Weller Brothers of Sydney established a whaling station at Timaru in 1839. According to a newspaper article from the time, the Caroline arrived in Timaru carrying a cargo of whale oil and whalebone. The article also notes that the Caroline had recently returned from a whaling expedition to the southern seas.

"The ship "Caroline" regularly dropped anchor after the Weller Brothers of Sydney established a whaling station at Timaru in 1839. According to a newspaper article from the time, the Caroline arrived in Timaru carrying a cargo of whale oil and whalebone."

"Mr Jahannes C. Anderson, in his “Jubilee History cf South Canterbury” says: ‘‘Joseph Price chief officer of the Harriet, left the boat in December, 1839, and started whaling on his own account at Ikorai, Banks Peninsula. Price shipped in September, 1931, on board the Caroline for a whaling cruise; but whether Caroline Bay was named after this ship, or after another Caroline, a whaler that frequented the coast up till the year 1835, is not known.” Timaru Herald - 12 APRIL 1934, PAGE 6

There is some debate about how the Bay got it's name, as there were other ships named Caroline that frequented the New Zealand coast in the 1800s.

At shore stations, as on whaleships, Maori were soon included in boat crews and were adept boatmen and harpooners. The shore stations' boats pursued right whales, which would enter bays on the high tide and leave them on the ebb. Sperm whaling continued but, as the demand for bone increased, more and more British, Sydney and French vessels turned to right whaling. In 1834 they were joined by the first American right whalers in New Zealand waters.

The whaling industry was short-lived, and the station was abandoned when they were preparing for a third season because the company failed. The men who lived there moved on from their temporary home, and it would be a few more years before Europeans settled permanently in the area.

"The French Ship Gustave, Declare, from Have fifteen months out, 1800 barrels black oil; 400 barrels this season at Pegansi Bay and the Tcmaroo Beach." New Zealand Colonist and Port Nicholson Advertiser, Volume I, Issue 13, 13 September 1842, Page 2 - New Zealand Colonist and Port Nicholson Advertiser, Volume I, Issue 13, 13 September 1842, Page 2

New Zealand was opened up to the world by the 35 of whaleship captains. Over four hundred islands in the Pacific were "discovered" and named by American whalemen, and the history of New Zealand is closely connected with the visits of New England whalers.

Further info

- Harvesting the sea: Sealing

- Harvesting the sea: Whaling

- Early Arrivals: New Zealand - Australia's New Frontier

- Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand Visit site run by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Visit site that contains the life stories of over 3000 New Zealanders. This site run by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- Christchurch City Libraries Visit the site with a handy range of factsheets on various aspects of New Zealand history.

The Sheltering Place: Yankee Sam of Timaru - whaler, settler, publican (26 Jul 1975). Aoraki Heritage Collection, accessed 23/06/2023, https://aorakiheritage.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/1096

Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1878. Very good overall. Color lithograph from 'The Instructive Picture Book' depicting two sperm whales, a whaling long boat between the whales, a waterspout in the middle ground and a whaling ship in the distance. This color lithograph made using a complicated printing method involving wood engraved detail, hand color and color lithography for the sky portion of the print; this is a multi-block color stone lithograph. With 'Antarctic Regions' below the image, and 'Sperm Whale' to the right; Plate LX in the upper right . - antarctic-regions-sperm-whale-antarctic

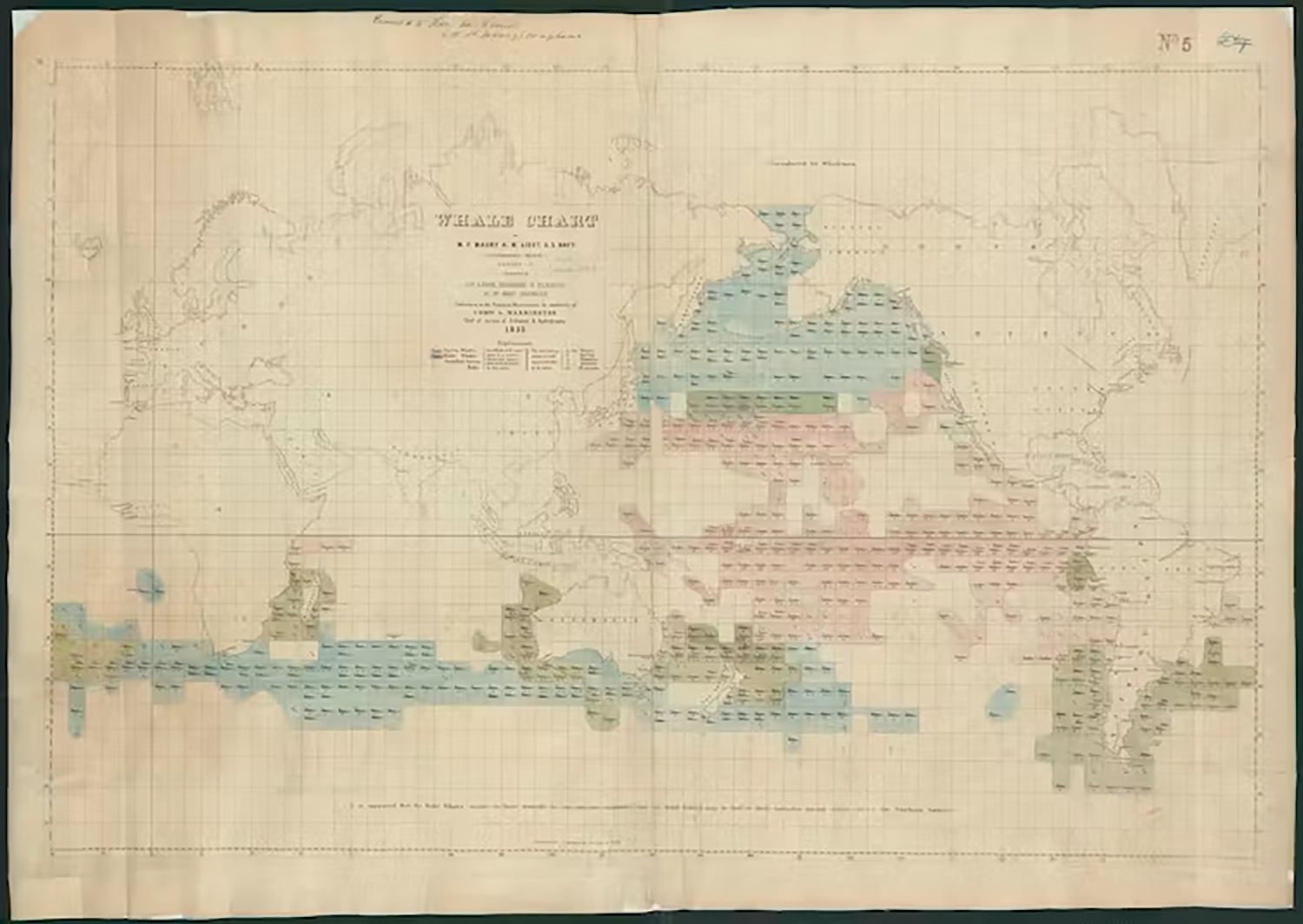

Map showing the distribution of whales across different seasons in the mid-19th century. Whaling connected Ngāi Tahu to the global economy in the early 19th century, providing new and sometimes mana-enhancing opportunities for trade, employment, and travel. As the whaling industry declined from the 1840s, some whalers (like Edward Weller) proved transient visitors. Many others, like Howell, remained with their families, though most were not as wealthy. Former whalers turned to fisheries, agriculture and trade. Their mixed communities formed the basis for settlements around the southern region such as Timaur's first perminant European resident Samuel Williams (Yankie Sam). Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library, CC BY-SA

Sam Williams (1817–1883) arrived at Timaru in 1839 with one of the Weller Brothers whaling gangs that worked from what is now the viaduct area of Caroline Bay. A Samuel Williams is on a crew list for the "Charles and Henry", a whaler that left Edgartown in 1836 bound for the Pacific. Later, after he moved on from Whaling he worked for the Rhodes family on Banks Peninsula. There he told the Rhodes brothers that the area was suitable for grazing sheep. Encouraged by this the Rhodes sought the lease that became Levels, run by George Rhodes.

Farming wasn’t for Sam though. He went to the gold fields of Victoria in 1851. While not successful prospecting, he did marry. Sam, his wife Ann and daughter Rebecca returned to Timaru in 1856. George Rhodes gave him his original cottage at the foot of George Street on the foreshore of Timaru. It was there in 1857 that Sam and Ann’s (Ann Mahoney b 1823 in Cork, Ireland) son William Williams was born - the first European child born in Timaru. A gin case was used as his makeshift cradle.

Moby-Dick Moby-Dick, Herman Melville’s greatest work, was published in. Melville had risen to prominence as a writer of adventure tales based on his own experiences at sea. In January he left Fairhaven, Mass., on the maiden voyage of the whaleship Acushnet. He deserted at Nuka Hiva in the Marquesas Islands, then joined the Australian whaleship Lucy Ann. After a bloodless mutiny the vessel returned to Tahiti. Melville made his way to the neighboring island of Eimeo (present-day Moorea), where he joined his third whaler, the Charles and Henry of Nantucket, Mass. - weekendamerica.publicradio.org

In March 2021 Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua gifted us the priviledge of using the name Pohatu-koko for the new playground, named after the stream running below it.

LEFT An early map of Timaru in 1860. RIGHT zoomed in area showing the labeled area "Pohatu Koko" next to the "old whaling station". This is where the traffic lights are at the end of Wai-iti Rd, and Evans St. The stream running through the area can be seen above. This stream is now piped under the viaduct at the bottom of Wai-iti Rd, under the playground and out sea at the Benvenue end of the boardwalk.

Courtesy of the National Library. Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga. Christchurch Office. Archives reference: CH1031, BM 245 pt 2, R22668176

The whalers used to draw their water from Whales Creek, but because the tide used to flow into this creek, they would have'to go as far as Nelson Terrace to obtain fresh water from the creek. ... The Whaler Caroline “Supplies to this station were brought by the whaling ship Caroline, and so they bay came to be known as Caroline Bay. This ship had an eventful history. At one tlme it was commanded by Captain Blenkinsopp, who brought the Waiau plains from the Maoris for a cannon. The cannon is mounted on an obelisk in the sware at Blenheim. The Caroline was later bought by John Jones who started a whaling station in Waikouaiti in 1840. The ship was subsequently wrecked at the mouth of the New River, Southland.

Because of bankruptcy, the whaling station was abandoned, and Dr Edward Shortland, the first man to record his journey on foot from Moeraki to Banks Peninsula in 1844, tells of the sorry sight this whaling station made. He wrote: ‘Many forlorn looking huts were still standing there; which, with casks, rusty iron hoops, and decaying ropes, lying about in all directions, told a tale of the waste and destruction that so often fall on a bankrupt’s property.‘

After the Timaru whaling station closed down," said Mr Vance. “the steersman, Sam Williams, went to work at the Rhodes' whaling station at Red House Bay. Banks Peninsula. Here Sam Williams told George Rhodes of the good sheep country lying to the south and the outcome of this was that the Rhodes Biothers took up all the land between the Pareora and Opihi Rivers and back to the Snowy Ranges. They also bought, the business area of Tirnaru. between North Street and Wai-iti Road and back to Grey Road—806 acres for £800.

Mr William Vance Traces History of Caroline Bay (12 Mar 1957). Aoraki Heritage Collection, accessed 07/06/2023, https://aorakiheritage.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/358 - aorakiheritage.recollect.co.nz/358

Captain Blenkinsopp married a Maori woman, the. daughter of a local ; chieftain, and purchased from Te Rauparaha the whole of Wairau Plain. Te Rauparaha repudiated the bargain and the incident had a direct bearing on the Wairau massacre m 1843 which was the beginning of the wars between Maori and pakeha. - paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/Captain+Blenkinsopp

Joseph, George and Edward Weller are immortalised in the folk song “Soon May the Wellerman Come” - circa 1850-1860.

“The song’s lyrics describe a whaling ship called the “Billy o’ Tea” and its hunt for a right whale. The song describes how the ship’s crew hope for a “wellerman” (an employee of the Weller brothers, who owned ships that brought provisions to New Zealand whalers) to arrive and bring them supplies of luxuries, with the chorus stating “soon may the wellerman come, to bring us sugar and tea and rum.” According to the song’s listing on the website New Zealand Folk Song, “the workers at these bay-whaling stations (shore whalers) were not paid wages, they were paid in slops (ready-made clothing), spirits and tobacco.” In the whaling industry in 19th-century New Zealand, the Weller brothers owned ships that would sell provisions to whaling boats. The chorus continues with the crew singing of their hope that “one day when the tonguin’ is done we’ll take our leave and go.” “Tonguing” in this context refers to the practice of cutting strips of whale blubber to render into oil. Subsequent verses detail the captain’s determination to bring in the whale in question, even as time passes and multiple whaling boats are lost in the struggle. In the last verse, the narrator describes how the Billy o’ Tea is still locked in an ongoing struggle with the whale, with the wellerman making a “regular call” to encourage the captain and crew. - denelecampbell.com/more-than-meets-the-ear/

Section on the map showing the Pohatu-koko stream.

Refernce to the "old native huts" at the foot of Wai-iti Rd intersection See map here

It is interesting to see the changes to the coastline. This rapidly changed when the new harbour was built.

1856 Map of the Province of Canterbury, Archives New Zealand. When you zoom in over Timaru, you can see the reserve for the township and Caroline Bay. Item reference: AGCO 8368 IA36 4/12 (R22420403)

Wellerman shanty is an old New Zealand composition.

The lyrics speak of men’s collective labour at sea. But behind the story of the whale hunt is one of cross-cultural interaction central to the success of the whaling industry, and critical in shaping the settlement of early 19th century New Zealand

Whaling in the 19th century world

Whaling brought newcomers to Aotearoa New Zealand in significant numbers from the early 1800s. Once predominantly American-based crews had exploited Atlantic whale populations, they moved into the Pacific to seek new hunting grounds.

These men sought profit in the form of oil and bone. Whale oil provided industrial lubrication and lighting for growing cities in Europe and the US. Baleen from whale jaws was used in much the way plastic is now.

New Zealand was one of their destinations. The Wellerman shanty refers to the heyday of whaling in the South Island. The Sydney-based Weller brothers established their first whaling station at Ōtākou (Otago) in 1831.

They and others such as Johnny Jones oversaw stations ranging from a few households to nearly 100 residents. These new settlements were dotted around the southern coasts from the late 1820s, often located near the paths of migrating right whales.

Read more: ShantyTok: is the sugar and rum line in Wellerman a reference to slavery?

Unlike deep-sea whaling in the Atlantic and northern Pacific, these newcomers practised shore-based whaling which required land to process the whales caught. The “tonguing” in the Wellerman lyrics refers to cutting strips of blubber to render into oil in large “try pots” — a challenging process aboard ship. The crew also required land on which to live and cultivate food.

Whalers in the Ngāi Tahu world

These shore whalers entered a Māori world. The success of a station was dependent on their relationships with local iwi as tangata whenua — in this case, Ngāi Tahu.

Newcomers had to negotiate access to coastal land and resources, and stayed for months, years, sometimes even decades. Because the industry was based on settlement rather than short refuelling stops, shore whaling fostered more intensive cross-cultural interactions in southern New Zealand than elsewhere in New Zealand or abroad.

Differing cultural expectations and miscommunication occasionally led to violence. More often, however, Ngāi Tahu and newcomers negotiated a relationship of mutual benefit. Whaling connected Ngāi Tahu to the global economy in the early 19th century, providing new and sometimes mana-enhancing opportunities for trade, employment, and travel.

Read more: Rock art shows early contact with US whalers on Australia's remote northwest coast

At the same time, Ngāi Tahu communities sought to incorporate whaling men into the rights and responsibilities of whanaungatanga (relations, connectedness). Intimate relationships and marriage were key features of this process, as historian Angela Wanhalla has shown.

Over 140 men had married Māori women in southern New Zealand by 1840, with these couples producing over 500 children. Edward Weller himself married Paparu, daughter of Tahatu and Matua. After her early death, Weller remarried Nikuru, daughter of rangatira (chief) Taiaroa, but left New Zealand without his wife and daughters after the Otākou station’s closure in 1841.

Ngāi Tahu in the whaling world

Many whaling stations became kin-based economies, with mixed families central to the labour and prosperity of both ship and station. As wives and partners, Ngāi Tahu women produced the food that sustained the station and supplemented the business of whaling.

While the Wellerman shanty’s “sugar and tea and rum” were imported as rations, potatoes, flax and pigs were locally produced, consumed, and exported for profit alongside whale oil and bone. Male relations also frequently worked in the industry, either on shore or as whaling crew.

This right to land for stations and settlement was based on principles of kaitiakitanga (guardianship). But in later decades the colonial government caused land dispossession through conversion to individual titles and Crown purchases.

Read more: Why it's time for New Zealanders to learn more about their own country's history

As the whaling industry declined from the 1840s, some whalers (like Edward Weller) proved transient visitors. Many others, like Howell, remained with their families, though most were not as wealthy.

Former whalers turned to fisheries, agriculture and trade. Their mixed communities formed the basis for settlements around the southern region: Bluff, Riverton, Moeraki, Taieri, Waikouaiti.

These early and intense interactions had a lasting legacy in Ngāi Tahu’s whakapapa (genealogy) and collective identity. The sustained contact between Ngāi Tahu and whalers also complicates the myth of whaling as simply a transient and masculine pursuit.

Whaling was indeed a gendered industry; crew were almost exclusively male. But they were also diverse. Native American, Aboriginal Australian and Pacific Islanders all found opportunities aboard ship and in New Zealand alongside Māori and Europeans.

Many of them, we must assume, would have sung or heard shanties like Soon May the Wellerman Come — though none might have expected their descendents in the 21st century to be humming them too.

William Vance, What would Sam Williams think?: Whale Creek on Bay Being Imprisoned, Water from Stream Attracted Early Whalers to Timaru (Nov 1959). Aoraki Heritage Collection, accessed 04/03/2025, https://aorakiheritage.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/6197

From the booklet: Timaru and South Canterbury, New Zealand 1950: the City and the Province to-day with some interesting glances at the past - 1950

The Caroline Bay Whalers – Key Points

From "First Settlers in South Canterbury" by William Vance

-

Early Whaling Activities (1835)

-

Whaling activity at Caroline Bay started when the ship Harriet brought men and equipment from the Blueskin whaling station in Otago.

-

30 shore-whaling stations operated along the New Zealand coast at the time, employing ~700 men and 90 boats.

-

These produced ~1,000 tons of whale oil annually, valued at £25,000.

-

Over-harvesting led to the decline: within 15 years, only 5 stations remained, producing 100 tons of oil per year.

-

-

Whaling Process and Dangers

-

Boats launched upon spotting whales; rowed four miles out to sea.

-

Precision seamanship was required to get close enough for a hand-thrown harpoon.

-

Harpooned whales would dive, dragging boats with them via 200-fathom ropes.

-

Rope entanglements were deadly – could capsize boats or maim/kill men.

-

Whales eventually surfaced and tired; boatmen would then finish the kill with a spade.

-

Dead whales were towed ashore and beached at full tide for blubber removal.

-

-

Processing the Whale

-

Blubber was quickly sliced and boiled in try-pots set in clay banks (location of modern Caroline Bay tennis courts).

-

Rendered oil was poured into casks stored at the base of the cliffs.

-

The smell attracted wild pigs from Timaru gullies, who fed on leftover blubber.

-

-

Life at the Whaling Station

-

Each station employed ~30 men, with the season running from May to October.

-

Profits averaged £1,000 per season; ordinary boatmen earned about 1% share.

-

Deductions for gear, food, and drink often left them in debt.

-

Despite risks and hard work, the men often complained.

-

Quote from the Piraki log:

“With the whalers and whaling, there’s always complaining…”

-

-

Social Life and Supplies

-

The whaling ship Caroline may have given Caroline Bay its name.

-

Supply ships brought varied cargo: tobacco, soap, clothes, tools, food, and even Jew’s harps.

-

Supply arrivals sparked parties with rum and revelry.

-

Huts were located in Beverley Road gully, near Māori whares.

-

Māori and whalers traded pigs and potatoes for tools and clothing.

-

Campfires, stories, songs, and camaraderie were common.

-

-

Water Sources and Environmental Changes

-

Water was sourced from Whale’s Creek (ran through Nelson Terrace and Hewlings Street to Caroline Bay).

-

High tide caused saltwater backflow into the creek.

-

In dry weather, a waterhole (later Ferry’s Pond) was used.

-

A major storm in 1882 washed away part of the cliff and an old whaling fireplace.

-

-

Decline of the Whaling Station

-

Whales became scarcer; station moved to Patiti Point.

-

Owners Weller Brothers (Sydney) faced bankruptcy.

-

Station abandoned by ~1840.

-

Piraki log (July 1, 1840): Timaru crew joined Price’s fishery after leaving their own.

-

Log (July 2, 1840): Crew signed new agreements.

-

-

Later Mentions and Legacy

-

1844: Edward Shortland noted the ruined state of the Timaru station.

-

1842: A French whaling ship wrecked on the Timaru beach with oil on board.

-

1846: New Zealand Spectator reported the station operating again under Mr. Chesland.

-

-

Notable Figure: Sam Williams

-

Former boat steerer and harpooner; American runaway sailor.

-

Employed by George Rhodes at Island Bay, Akaroa.

-

Despite his drinking, Rhodes trusted him and became a loyal friend.

-

Williams likely explored inland, reporting promising sheep country.

-

Rhodes and Williams became the first runholders of South Canterbury after driving sheep from Banks Peninsula.

-