Tuna (eel) are a very significant, widely-valued, heavily-exploited, culturally iconic mahinga kai resource. - Geoff Cloake

Timaru’s coastline was abundant in marine life and was an important source of kai moana for Māori.

Kai such as tuna (eel) and inaka (whitebait) patete (fish), and kōareare (the edible rhizome of raupō) were abundant in the area.

Mahika kai (to work the food)

relates to the traditional value of food resources and their ecosystems, as well as the practices involved in producing, procuring, and protecting these resources.

Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua is the principal Māori kainga in the Aoraki region from the Rakaia to the Waitaki and back to the main divide. They are one of the 18 Paptipu Rūnanga that are leaders amongst their southern communities and are based with the marae in South Canterbury.

They primarily claim descent from the hapu Kāti Huirapa and affiliate to the iwi Waitaha, Rapuwai, Kāti Hawea, Kāti Mamoe and Ngāi Tahu.

The ancestors of the Arowhenua people were well established between the Rakaia river to the north, Waitaki to the south, and back to the central mountain ranges of Aoraki and his brothers (Southern Alps).

Prominent Huirapa ancestors, trading trails, settlements and events extend beyond these areas, but the local region isthe most concentrated signs of activity and occupation of Rapuwai, Waitaha, Kāti Hawea, Kāti Mamoe, and Kāi Tahu.

The many lakes, rivers, and corridors of native bush provided rich hunting and gathering grounds, with a long established cycle of gathering, travelling and trading was prevalent into the late 1800’s.

Some of the earliest signs of occupation in the region are the many rock art sites throughout South Canterbury.

LEFT An early map of Timaru in 1860. RIGHT zoomed in area showing the labeled area "Pohatu Koko" next to the "old whaling station". This is where the traffic lights are at the end of Wai-iti Rd, and Evans St. The stream running through the area can be seen above. This stream is now piped under the viaduct at the bottom of Wai-iti Rd, under the playground and out sea at the Benvenue end of the boardwalk.

Courtesy of the National Library. Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga. Christchurch Office. Archives reference: CH1031, BM 245 pt 2, R22668176

Section on the map showing the Pohatu-koko stream.

Whales Creek Railway Viaduct at the foot of Wai-iti Rd and Evans Street, Timaru, New Zealand, 1904-1915, Timaru, by Muir & Moodie. Purchased 1998 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds. Te Papa (PS.001051)

1947 - View to the south Canterbury town of Timaru with Caroline Bay with Evans Street in foreground looking south over the CBD and outer suburbs. You can see the stream running to the sea. Aerial photograph taken by Whites Aviation. Tiaki IRN: 720135. Tiaki Reference Number:: WA-06402-F - PA-Group-00080: Whites Aviation Ltd: Photographs

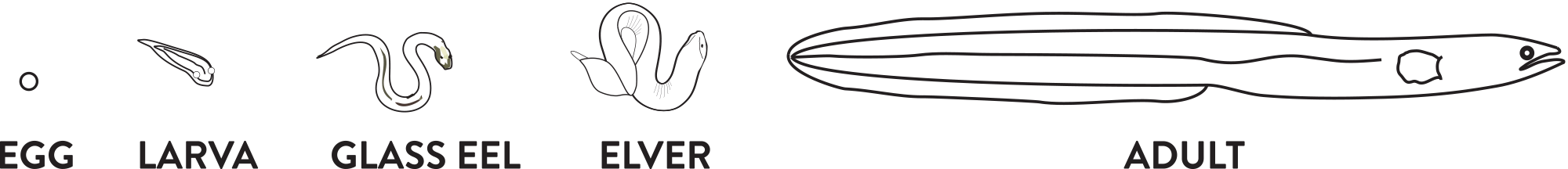

The tuna go on a massive migration journey from New Zealand to the Kemadec Trench near Tonga. They produce eggs which float back to the shores of New Zealand. Adult freshwater (living in streams, lakes, wetlands) can live up to 100 year old. They feed on insects, snails, fish, and even birds. Female tuna can reach 2 meters long. They leave their home and migrate thousands of kilometres from the fresh water to the sea water into the Pacific Ocean to release eggs and sperm in a process called spawning. Their eggs hatch far in the South Pacific Ocean near Tonga. They are very small and can only be seen using a microscope. The fertilised eggs then develop into larvae called leptocephali, which travel back to New Zealand drifting via ocean currents over 9-12 months and eventually arrive in New Zealand. Eels then enter our rivers as small juveniles that are known as glass eels. They are about 60-75 mm long. After several weeks in the fresh water the darken an become known as an elver. They migrate upstream during the summer. They are able to climb obstacles until they get to 120mm length.

Tuna - eel

Tuna is a generic Māori word for freshwater eels. Māori have over 100 names for eels.

They live: in lakes and rivers connected to the sea.

They eat: small insects larvae, snails, midges and crustaceans. As their mouths get bigger, they can eat kōura (freshwater crayfish), fish, small birds and rats. When scared they bite!

Did you know: they are the largest fish in Aotearoa freshwaters

There are three tuna eel species in NZ: The longfin eel, known as tuna, is one of the largest eels in the world.

LONGFIN EEL: (Anguilla dieffenbachii) Max size: 2m, 25kg

SHORTFIN EEL: (Anguilla australis) Max size: 1.1 metre, 3kg

AUSTRALIAN LONGFIN EEL: (Anguilla reinhardtii), Max size: 2 metres, 21kg

They are a taonga species: central to the identity and well being of many Māori and are a significant mahinga kai (food).

Traditional knowledge

Tuna is a generic Māori word for freshwater eels; however, but there are a multitude of names that relate variously to tribal origins, appearance, coloration, season of the year, eel size, eel behavior, locality, and capture method. Tuna are arguably one of the most important mahinga kai resources for Māori. They were abundant, easily caught, and highly nutritious. Tuna were especially important in southern New Zealand, where it was too cold to grow some crop foods. Some tuna were considered sacred, and on occasion large eels were fed and noted to be treated as gods.

Many methods were used to take tuna - a common method for capturing adult tuna was using baited hīnaki, while juvenile tuna were taken on their upstream migration in bunches of fern. Tuna were often stored live in large pots for later consumption or hung to dry.

Tuna or freshwater eels are a very significant, widely-valued, heavily-exploited, culturally iconic mahinga kai resource. Although there are many stories and legends of tuna spawning in freshwater, what is certain is that all freshwater eels spawn at sea. Adult freshwater (living in streams, lakes, wetlands) can live up to 100 year old. They feed on insects, snails, fish, and even birds. Female tuna can reach 2 meters long. They leave their home and migrate thousands of kilometres from the fresh water to the sea water into the Pacific Ocean to release eggs and sperm in a process called spawning. Their eggs hatch far in the South Pacific Ocean near Tonga. They are very small and can only be seen using a microscope. The fertilised eggs then develop into larvae called leptocephali, which travel back to New Zealand drifting via ocean currents over 9-12 months and eventually arrive in New Zealand. Eels then enter our rivers as small juveniles that are known as glass eels. They are about 60-75 mm long. After several weeks in the fresh water the darken an become known as an elver. They migrate upstream during the summer. They are able to climb obstacles until they get to 120mm length. - niwa.co.nz/life-cycle

ABOVE: Map of the pacific ocean and "ring of fire" showing the edge of the techtonic plate that forms the Alpine Fault line in New Zealand, and the Kermadec and Tonga Trench's. The Kermadec Trench is one of Earth's deepest oceanic trenches. Every year, a proportion of eels mature and migrate to sea to spawn. Downstream migrations normally occur at night during the dark phases of the moon, and are often triggered by high rainfall and floods. National Geographic

Location of archival pop-up tags ascent locations on four longfin eels tagged and released from south of Christchurch. The tags were programmed to release from each eel at a different time. Once the tags came up to the ocean surface they sent all of the data they had been collecting via satellite to NIWA scientists eagerly awaiting the results. Credit: Don Jellyman

'Ka hāhā te tuna ki te roto; ka hāhā te reo ke te kaika; ka hāhā te takata ki te whenua' - If there is no tuna (eels) in the lake; there will be no language or culture resounding in the home; and no people on the land; however, if there are tuna in the lake; language and culture will thrive; and the people will live proudly on the land - Nā Charisma Rangipuna i tuhi

They are legendary climbers and have penetrated well inland in most river systems, even those with natural barriers.

Elver eels wiggling their way into Lake Opuha via the Elver Bypass 2023. Photo's Supplied by Opuha Water Limited (OWL)

Elver bypasses on the Opuha Dam infrastructure ensure tuna/eels can continue their migration up the Opuha River into Lake Opuha. Here you can see little Elver (juvenile tuna/eels) at the Opuha Dam. They wiggle their way up the elver bypass, a special pipe which runs up the side of the 50m high dam from the Opuha River, and drops down the other side into the lake.

Elvers migrate upstream, typically between late November and early March, when temperatures reach about 16°C. They are able to climb damp vertical surfaces until they are about 12 cm long, at which size they are too heavy to stick using surface tension.

Most high dams in New Zealand are now equipped with bypasses, eel ladders and/or have trap and transfer operations. What is reasonably uncommon in NZ is monitoring to understand the effectiveness of the bypasses. To help fill this gap in knowledge, Opuha Water Ltd (OWL) are currently doing some small modifications to the elver bypass boxes to enable their team to temporarily catch and count how many elver are going into the lake.

OWL doesn't have a mechanism to provide for adult tuna to migrate downstream but are actively pursuing opportunities to establish a trap and transfer programme, whereby adult eel are netted and transferred downstream below the dam where they can then migrate out to sea.

Above: The Lake Opuha Dam was built in the late 1990's. Lake Opuha is a 700 hectare man-made lake, built as an irrigation reservoir as an infrastructure project undertaken by the community of South Canterbury. The Opuha Dam, (where the North and South Opuha Rivers meet near Fairlie), also generates electricity before water flows on to meet the Opihi River further down stream.

As well as the increased value of the farms and the farming activities, the reliable irrigation has provides growth for various vegetable processing exporting operations in Washdyke and has supported the growth of the massive dairy processing facility at nearby Clandeboye.

The 7MW power station contributes to the local electricity network and the revenue from the electricity sales accounts for approximately half of the company’s income.

In this map you can see the Waimataitai Lagoon before it was drained and turned into a park. The stream was piped underground and can be seen at the golf course. Miscellaneous Plans - Borough of Timaru, South Canterbury, 1911 - T.N. Brodrick, Chief Surveyor Canterbury ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/IE31423732

Above you can see the stream that runs past Timaru Top 10 Holiday Park. This runs under Ashbury Park to sea. The park used to be a large tuna weir. "Waimātaitai was a hāpua (lagoon) renowned as an important source of mahinga kai. In 1880 Hoani Kāhu from Arowhenua described Waimātaitai as “e rauiri” (an eel weir) where tuna (eel) and inaka (whitebait) were gathered. This saltwater lagoon was eventually lost in 1933 due to changes in sediment drift caused by the creation of the Port of Tīmaru." - kahurumanu.co.nz/atlas

What was once a lagoon, is now Ashbury Park. Aerial view of Timaru, showing Caroline Bay, harbour and town between 1920 and 1939. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections FDM-0690-G

This 1874 sketch is from Benvenue Cliffs looking to Dashing rocks. You can see the spit that used to be here and the lagoon on the left. Eliot was here taking measurements to draw the Harbour construction plans. After the breakwater was started in 1878, it was noticed that the shingle bank was being eroded. In the early 1800s, basalt rock was brought in to protect the bank and the rail way behind it. By the 1820s the lagoon was under threat, it was filled in and by 1935 the Waimataitai Lagoon was gone.

- Eliot, Whately. 1874, Near Timaru, N.Z., Sept. 23, 1874 , viewed 27 April 2023 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138582026

Tuna / eels in the steam that runs beside the holiday park. This stream connects to a underground drain under Ashbury Park, Waimataitai Beach. Photo Supplied by Timaru Top 10 Holiday Park

Niwa has published an climate report "Understanding Taonga Freshwater Fish Populations in Aotearoa-New Zealand" here: https://waimaori.maori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Understanding-Taonga-Freshwater-Fish-Populations-in-Aotearoa-New-Zealand.pdf